A short guide to “friend-shoring” and its market implications

“Globalization is not something we can hold off or turn off . . . it is the economic equivalent of a force of nature — like wind or water.”

Bill Clinton (American 42nd US president (1993-2001))

Twenty years after …

“Going forward, it will be increasingly difficult to separate economic issues from broader considerations of national interest, including national security…On some issues, like trade and competitiveness, this will involve bringing together partners that are committed to a set of core values and principles…Favoring the friend-shoring of supply chains to a large number of trusted countries, so we can continue to securely extend market access, will lower the risks to our economy as well as to our trusted trade partners.”

U.S. Treasury Secretary J. Yellen (2022)

Recently much traditional and digital ink has been spilled over the subject of globalization, slowbalization, and in the most extreme scenario: outright deglobalization. Understanding global trade dynamics and how these could change are a central element of our macro view. The metamorphosis of global trade may have long-lasting effects on growth and inflation. Let’s pay close attention to it.

We do not have the ambition to have a complete panoramic vision of this vast phenomenon, and apologies in advance if some of our conclusions may seem partial. The purpose of this post is to summarize our main takeaways on some emerging trends in global trade and will analyze the potential market implications. Hopefully what follows will be useful food for thought for the reader to help her/him formulate a view around this subject.

Let’s start with an observation: our rules-based multilateral global trade system, established in the aftermath of WWII is unraveling right in front of our eyes.

For over seven decades, free trade has been the center of gravity of our world. There has been an incredibly broad consensus that a global, fair, free trade system, based on the precepts of “national treatment” and “most-favored nation”, was not only important for economic prosperity but also geopolitical reasons. A win-win that benefits all!

For guys that grew up like me between the 80s and the 90s, as free traders, globalization has been an unstoppable force. We grew up with it. I remember, once Clinton said: globalization is like the wind. Nobody can stop the wind. It felt inevitable that the global economy was going to just get more integrated. We were walking along a one-way street, where we were just moving in one direction: toward a deeper integration.

What brought us to this critical inflection point?

When D. Trump entered the scene in 2017 after a very protectionist, anti-China presidential campaign, the change seemed very abrupt. For the first few years, it felt like we were going through an aberration and it seemed natural that we would have snapped back to the old course of action. But that view was maybe naive. It turns out that Biden shares several views with Trump regarding trade policies. Biden has done nothing about China tariffs. He actually extended – under the CHIP’s act – restrictions on sales of semiconductors technology to China. So, let’s take a step back, when did things start to change?

Source: Cato Institute, World Bank

Source: McKinsey Global Institute

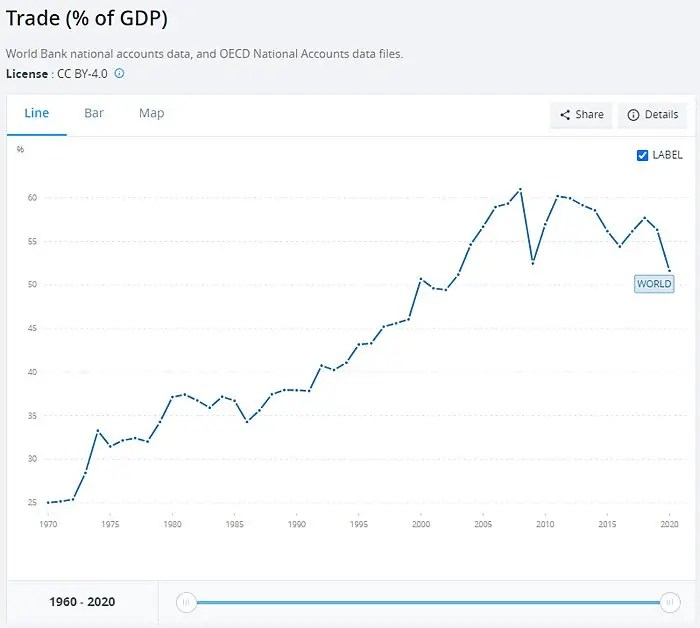

It was probably when the GFC was in full swing that the first cracks started to appear, and resistance to globalization broadened and became bipartisan. Obama during the 2008 presidential campaign criticized NAFTA. William Daley, Obama’s chief of staff, also warned that “free traders and pure market believers” need to overcome their dogmatism if they want the US to dig itself out of the economic crisis. This is probably the point in time when hyper-globalization reached its peak. The two charts above, the first one on global trade, and the second on capital flows are probably a good illustration of such an inflection point.

A couple of important systemic shocks further cracked the consensus around free trade. The first one has been the pandemic. The COVID pandemic has been very important in reminding us that global trade not only brings us incredible benefits but also brings a certain amount of risks and vulnerabilities. The second important shock was the war in Ukraine. Why is the Russia-Ukraine war so important from the global trade perspective? The conflict highlights a critical issue: economic interdependence can be weaponized.

There is now an increased and broad recognition that our expectations were maybe too optimistic. We are entering a phase where the original cooperative spirit that underpinned the rise of globalization is going through a geomagnetic reversal. The aspiration for a single stable deeply interconnected global trade system is falling apart.

The Thrill is Gone!

Where are we heading to?

In what direction is now the compass needle pointing? What is the new N.O.R.T.H.?

It is time to recalibrate. It seems almost inevitable that we are heading toward a more fragmented system consisting of self-selected trade blocs.

These new geoeconomic blocs are not built to merely maximize economic efficiencies. They are built around the geopolitical calculus to deepen economic relationships among countries that share a common set of values, a common philosophy, and a common political vision. In other words, this is called “friend-shoring”. Because it has become obvious that economic interdependencies can be weaponized, business relationships must be built among friendly countries.

Before we start, let’s get some lexicon right…

So we understand each other!

With terminology continuously changing, it can be hard to stay informed. What exactly is friend-shoring? So, here below is a quick rundown of manufacturing and operations models.

Outsourcing. That is when companies hire outside providers to perform services or create goods that traditionally were managed in-house. Outsourcing allows the company to invest energy and funds in areas where they have an effective edge.

Off-shoring. Offshoring refers primarily to the practice of moving business activities from one country to another. Offshoring can be combined with outsourcing, meaning that a company has relocated a practice to a different company in a different country, but the terms are not mutually inclusive. Offshoring can be divided into three, different models: nearshoring, far-shoring, and friend-shoring.

Far-shoring. Farshoring is the act of bringing a company’s functions to a country that is far from the company’s host country.

Near-shoring. Nearshoring is exactly the opposite of far-shoring. It is the practice of bringing company functions to a different country than the companies’ home country, but to a country that is geographically proximal.

Friend-shoring. Friendshoring, as opposed to nearshoring and onshoring’s focus on geography, is instead primarily defined by political and cultural proximity.

On-shoring. That’s the opposite of Off-shoring. More recently companies have chosen to engage in onshoring. This is the practice of bringing a business function from a different country, back to the home country. Over the recent years, onshoring has gained traction as a way of taking back control over supply chains as our globalized economy has become more turbulent.

The big picture.

Where are the most critical interdependencies? In this section, we are picking up on a discussion paper by McKinsey Global Institute “Global flows: The ties that bind in an interconnected world”.

No region is self-sufficient, and all are mutually interdependent, joined by large corridors of trade flows that cross the world.

Source: McKinsey Global Institute

Net Inflows and net outflows chart.

Source: McKinsey Global Institute

Every region imports more than 25 percent of at least one important type of resource or manufactured good that it needs, and often much more. Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia are net importers of manufactured goods; they import more than 50 percent of the electronics they need. The European Union and Asia–Pacific import more than 50 percent and 25 percent, respectively, of their energy resources. North America has fewer areas of very high dependency but relies on imports of both resources, notably minerals, and manufactured goods.

Looking at the incredible interdependence across regions, outright deglobalization would be economically and financially impossible to achieve. Companies do not want it and ultimately consumers, used to cheap prices, would not accept it either.

What is then Globalization 2.0 going to look like?

Friend-shoring strategy – The Smile Curve.

The first strategy is probably to retain as much as possible the most value-added production stages. The Acer’s founder Stan Shih has been one of the pioneers in conceptualizing global value chains. He developed the now famous “Smile Curve” to represent the value added in each segment of the value chain:

In early 2000, the geographical distribution of the various production stages was looking like this:

Twenty years later…..

No big change really! Using trade and labor cost data, countries in this analysis can be plotted along the “Smile Curve”. The results show that their positions along the curve have been largely stationary over the past two decades. Advanced economies like the United States, Japan, and South Korea occupy the higher ends, while China and Southeast Asian countries have continued to hover around the bottom.

Sectors to watch

The second strategy for Reglobalization 2.0 is about keeping control of certain key strategic sectors. The following analysis is built on a report by the White House “Building resilient Supply Chains, Revitalizing American manufacturing, and fostering broad growth”. Let’s go through a quick rundown of the main takeaways.

Sector 1: Semiconductors.

Semiconductors are probably at the heart of the trade war between China and the US. That’s because, in many ways, our world is “built” on semiconductors. In fact, the semiconductor industry makes vital components for the technologies we all depend on.

Source: KLA

As we can see from the chart above, the Digitazion of Everything, the IoT ecosystem is creating a world in which every product, every piece of industrial equipment, and every healthcare device is connected to larger networks. The West actually controls most of the value chain with the important exception of the actual manufacturing of microchips.

Source: Alex Capri and Hinrich Foundation

There are currently only five foundries of significant scale: GF, Samsung, SMIC, TSMC, and UMC. Collectively, these five foundries accounted for 85% of worldwide foundry revenue in 2021, with SMIC, TSMC, and UMC accounting for approximately 70% of foundry revenue in 2021, according to an April 2022 Gartner Semiconductor Foundry Worldwide MarketShare report. More importantly, Gartner estimates that approximately 74% of foundry wafer fab capacity in 2021 was located in Taiwan or China. For this reason, the Biden administration has been pushing ahead with plans to bring onshore production of key components in everything from phones to military jets. The political response has been swift and so far successful with TSMC starting to build a few manufacturing plants in the US. Once production starts, in 2024, it will cover US semiconductors demand.

Legendary investor Peter Lynch once said, “When there’s a war going on, don’t buy the companies that are doing the fighting; buy the companies that sell the bullets.” That advice can be applied to chipmakers. Numerous companies are fighting for control of end markets like cloud computing, consumer electronics, 5G, and electric cars, but all of them depend heavily on semiconductors.

So, who controls the value chain, in other words, who sells the bullets? The West.

Sector 2: Telecommunications, 5G infrastructure

China now is the largest 5G market in the world, accounting for 87 percent of 5G connections worldwide. Huawei and ZTE of China have been the global leaders in providing 5G infrastructure including base stations. The main competitors Ericsson, Nokia, and Samsung are lagging behind.

Some time ago, the United States accused Huawei of using its installed equipment to collect intelligence for the Chinese government and banned Huawei equipment in US telecom networks as well as sales to the company of high-tech products, either produced in the United States or internationally using US inputs. The United States has also waged a persistent campaign to dissuade other countries from using Huawei equipment to limit the risks of being spied upon by China. Chinese smartphone giant Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd. is believed to have finally used up its stockpile of homegrown advanced chips as a result of U.S. sanctions enacted against the company during Donald Trump’s administration.

In short, the US and its close allies will intensify their efforts to develop telecom equipment onshore or from friendly countries. Chinese equipment, instead, will continue to be used by most other countries, especially in the developing world. Consequently, the telecom market will decouple and be built around two competing systems, with different technological and regulatory standards.

Who controls the business? The West.

But, the story may not be over. I would closely watch China’s response, as tensions around Taiwan may be far from over.

Sector 3: Equipment needed for the green energy transition.

Solar panels, wind turbines, and high-capacity batteries are necessary equipment for the energy transition to produce solar and wind energy and to power electric vehicles. China has long prioritized these sectors in its development plans already in 2015 when it launched its Made in China 2025 program. China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have been able to dominate the global supply chains of these products. The United States and Europe have yet to develop systemic plans to address China’s dominance in these sectors.

As of now, Chinese companies have practically cornered the market of these products, controlling more than 80 percent of all manufacturing critical for the production of solar panels, including more than 95 percent of the world’s production of polysilicon and wafers.

Who controls the energy transition? China.

It would seem that especially Europe finds itself between a rock and a hard place, transitioning from fossil fuels sold by Russia, into green energy built with Chinese technology. It feels like the bill it will be expensive!

Sector 4: Active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs).

China now produces about half of the world’s APIs and an even higher portion of several key ingredients. For example, China produces 80% of the global market for heparin (used for blood thinner) and 86% of antibiotics like tetracycline and doxycycline. Furthermore, China controls an even larger share of the world’s key starting materials (KSM), which are the raw chemicals used to make APIs.

It is also instructive to examine the case of India. Over the years, India has earned a reputation as the world’s pharmaceutical hub. But the reality may be different. India, in fact, accounts for only 20 percent of the global supply of generic drugs and relies on China for 80 percent of the APIs. So, despite talks about reshoring or friend-shoring the supply of critical pharmaceutical products, nothing much has happened. The pressure on drugmakers to lower drug prices has made it practically impossible for them to move their supply chains away from China.

Who controls the sector’s value chain? Again, China.

Sector 5: Strategic and critical minerals

Rare earth elements — in short REE — are a group of seventeen minerals. They are generally classified as heavy and light rare earths. These metals are critical for the production of several modern technologies from smartphones, hard disk drives, electric vehicles, military defense systems, clean energy, and medical equipment.

China possesses 36.7% percent of world reserves — compared to 1.5 percent by the United States — but controls over 50% of the mining of REEs and 90% of their refining and processing. The dominant position of China can be traced back to a campaign it launched in 1975 to develop and attain dominant world positions in strategic materials like rare earth elements as well as new materials.

The US government has invested in and revived companies to mine rare earths in Colorado. Today US production already exceeds 40,000 tons of REEs per year—second only to China—, but still, it has to import refined and separated REEs from China. The EU has made statements about securing the supply of rare REEs but has yet to implement any concrete projects. Altogether, several initiatives have reduced the share of China in the world’s supply of rare earths. However, China still maintains a position of clear advantage and it is not clear if the West can achieve its goal of self-sufficiency in these critical minerals anytime soon.

Who controls the value chain? China

What is the collateral damage?

Friendshoring is appealing politically. However, it is not something that can be implemented quickly. After all, global supply chains for each product have evolved over decades.

The recalibration of the supply chains will require interventions: massive Capex, financial subsidies, tax giveaways, and regulatory forbearance. All of the above is not without costs.

It is clear in what direction friend-shoring will impact inflation over the long run. Not only because production costs will increase, but also because those companies that are highly dependent on sales to China, will be tempted to compensate for the loss in revenues with hikes in prices. China will also try to maximize its gains in those sectors where it has achieved a solid positional advantage.

Friend-shoring Hotspots

Which countries could potentially benefit the most from a decoupling between the US/Europe and China?

One method to identify emerging trends could be to take a look at the change in US imports since 2018, the year when the first tariffs on Chinese imports were introduced. Over the last few years, China moved from being the second-largest import source in the US to the fourth position after EU27, Mexico, and Canada.

Source: WorldBank (WITS), Allianz Research

The biggest beneficiaries so far have been, Vietnam, Taiwan, South Korea, and India in Asia and EU27.

The second methodology, as discussed in “Globalization 2.0 Can the US and EU really friendshore away from China?” by Allianz Research, would be based on the analysis of comparative advantage.

Looking at global value-chain trade, and thus exports of goods that are produced over multiple countries, China is not the most competitive. manufacturing center. In fact, taking into account several factors, from competitiveness to the absence of geopolitical tensions with the US and the EU, the discussion paper finds that Mexico, South Korea, Japan, Vietnam, Indonesia, Brazil, and Malaysia could be best positioned for friendshoring. Surprisingly according to this analysis, India, probably the number one hotspot in the friendshoring race, is lagging behind in terms of efficiency.

Source: WorldBank, Allianz Research

The third methodology is based on political proximity.

Source: PEW Research

The chart above displays which countries see the U.S. as their top ally. The outcome is not very dissimilar from the one based on the other two methodologies presented above. One significant top entry would be the Philippines in Southeast Asia. In Africa — another potential emerging hot spot for the new reglobalization — Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa could become potential targets for friendshoring.

The bottom line is: deglobalization is off the table and offshoring is here to stay. Companies will continue to run their operations in the locations that make the most financial sense, but at the same time, a lot of companies are engaged in rethinking their China-centric supply chains. There will be winners and losers and a few investment opportunities along the way.

Investment Implications

I will try to summarize our key takeaways on the market implications of friend-shoring in a few bullet points.

First of all, Inflation. It is probably worth noting that the friendshoring process will cause structurally higher inflation. Don’t get me wrong. This does not mean that the cyclical component of inflation will not wildly swing from an inflationary regime to outright deflation, during recessions. But over the cycle, structural inflation will be higher than what we got used to over the last few decades. The reason is that we are experiencing a fundamental shift in the inner workings of our economies. We got used to the idea that our economies are guided by free markets. But we are now in the process of moving to an economic system where a large part of the allocation of resources is not left to markets anymore given the growing symbiosis between governments and companies. I believe it is always inflationary when the government plays a significant role in the allocation of capital.

Second, Capex. The redesign of our global value chains will involve massive investments in the key strategic areas of technology, energy, defense, etc. With this regard, I do really struggle to see how real interest can stay positive for a period longer than 6 to 12 months. Central banks are now frontloading interest rate hikes, but financial repression will soon be back on the table as inflation will start to revert to a more “normal” level of 3-4%.

Third, global portfolios and emerging markets. The example of Russia last year, has clearly shown the risks associated with investing in ‘unfriendly’ jurisdictions. The playbook for investing globally is going through a fundamental change. Investors will have to pay close attention to where they allocate their capital if they don’t want to run the risk to remain stuck with their investments as happened with Russian sovereign and corporate issuers. The weaponization of financial relationships will probably remain a topic for the foreseeable future. Adopting a more focused investment approach when managing emerging market exposures will be critical. Sticking to friendly shores will be a big plus!

Fourth, regionalization of the U.S. Dollar. Globalization of the value chains and globalization of the US dollar go hand in hand. As we are in the process of redesigning the geographical layout of global production chains, the use of the US dollar in global trade will change with it. It is inevitable that the US dollar will no longer be employed in transactions among countries not belonging to the sphere of influence of the recalibrated globalization.

Fifth, trend-following is coming back into vogue. Trend-following is a strategy that tends to perform better in periods of significant regime shifts. After almost 15 years of relatively poor performance, in the aftermath of the GFC, the strategy, which is now heavily under-represented in investors’ portfolios, may become again a very important tool for diversification as we are going through many fundamental and lasting changes on many levels.

Let’s be open-minded and let’s get ready to adapt our investment playbook to the fast-changing landscape. The old good days for quiet buy and hold may be gone for now.

Happy 2023!

InflectionPoint

Disclaimer

All views expressed on this site are my own and do not represent the opinions of any entity with which I have been, am now, or will be affiliated. I assume no responsibility for any errors or omissions in the content of this site and there is no guarantee for completeness or accuracy. The content is food for thought and it is not meant to be a solicitation to trade or invest. Readers should perform their investment analysis and research and/or seek the advice of a licensed professional with direct knowledge of the reader’s specific risk profile characteristics

Leave a Reply